Nadja Cech teaching Chemistry with “Yes, and”

by Omar Ali and Nadja Cech

Here we present ‘Yes, and,’ a concept derived from improvisational theatre, as a teaching-learning methodology that supports engaged experiential learning. In this approach, the leader of the group and co-participants affirm each other and creatively build on what any and all bring to the conversation and activity at hand. The approach can enhance academic excellence by cultivating confidence, creativity, and collaboration.

We have always done things before we knew what we were doing. Improvising is one of the defining characteristics of our species. It is what has made it possible for you to read these words, carry on conversations with others, or tie your shoe laces. At some point, you didn’t know how to walk or talk (or their equivalents), but you took baby steps . . . and here you are. As adults, by “performing” ahead of ourselves (by doing things before we know how to do them—i.e. improvising), we learn and grow. Improvising, the adult form of children’s play, makes us the creative, revolutionary, beings that we are. It accounts for our incredible species development and all things great (and maybe not so great) that we have collectively produced in society, in history.

The following are examples of how the co-authors of this article, in our capacities as teachers, improvise to create engaged experiential learning opportunities with students inside and outside of the classroom. In particular, we will illustrate the approach called “Yes, and,” a simple, yet powerful technique drawn from improvisational theatre, to create environments that support the development of our students.[1]

“Yes, and”

In our separate realms and largely on the campus of The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, we (Nadja and Omar) have spent thousands of hours working with hundreds of students. Over the past two decades, both in and out of our respective classrooms, and in very different disciplines, we have come to practice a remarkably similar approach—a methodology—in our teaching and mentoring. We consistently and enthusiastically affirm and encourage our students in their social-emotional-intellectual development. To accomplish this, we practice “Yes, and.” In a nutshell, the essence of “Yes, and” is to respond positively to what others bring to a conversation or activity, and then to take what they offer and further build on it. In the context of improvisational theater, this means paying careful attention to what a fellow actor is trying to accomplish and working supportively with them to pull it off. For example, if our partner in an improv scene offers us an imaginary flower, we take it from their hand and say, “Oh, what a beautiful flower.” We do not respond with, “What flower? I don’t see any flower.” In the context of classroom teaching, the “Yes, and” approach looks a little different (more on that later), but the core concept is the same. We, the teachers, work with our partners (our students) to collectively create something new.

Facilities Operations Employees at UNCG Participating in Omar Ali’s workshop series designed to build community through improvisation and play.

Obuchenie and Development

As professors, we are principally concerned with our students’ development, by which we mean the increased capacity to recognize opportunities and act on such opportunities productively. We are convinced that our ability to facilitate the development of our students is not so much the product of our disciplinary-specific training or areas of expertise, but of the effectiveness of our consistently treating them as fellow and able co-learners, a process that is facilitated by “Yes, and.” When relating to our students, we strive to interact in the context of what the twentieth-century Russian psychologist, methodologist, and educator Lev Vygotsky describes as obuchenie, the Russian term we understand to mean “teaching-learning.”[2] As opposed to the separation that is traditionally made between “teacher” and “student” or “teaching” and “learning,” obuchenie combines these into a single concept. Obuchenie, as activity, is in sharp contrast to the notion of “teacher” as the fount of knowledge, which is poured into the heads of students. Rather, we seek to co-create with our students social environments or spaces in which learning can take place. As part of this process, to use Vygotsky’s formulation, we relate to our students as “a head taller” than they are.[3]

A vivid illustration of the concept of relating to others ahead of themselves may be seen in Vygotsky’s example of how we as a species learn language. Toddlers, for instance, will babble, while those of us who are older (i.e. language speakers) relate to them as if they are speaking coherently. A toddler may waddle along and point up at a bottle of milk and exclaim “bofflee!” In that specific context we’ll likely respond by looking at them and saying, “You want the bottle? … Okay, here you go.” By our speaking to babbling toddlers as if they themselves are able to understand and speak clearly, they begin to understand and eventually do become language speakers. Put another way, we don’t require toddlers to master our spoken (or other) language before we speak to them. If that was the case, they would never learn how to speak.

While the process of learning language in our species unfolds “naturally,” as we move beyond our toddler years, we tend to be inconsistent in relating to each other as capable of continuing to develop. And this is where “performing” or “improvising” comes in. In other words, we have to (sometimes) pretend with others as if they are more capable than they are in order to help them get there.

Omar practices “Yes, and” with participants in Spectrum, a UNCG campus support group for students on the autism spectrum.

Performing as Educators

As college educators, we often feel social and institutional pressure to deliver content knowledge over and above anything else. Yet, as the developmental psychologist Lois Holzman and philosopher Fred Newman point out in The End of Knowing, “learning leads development.”[4] In other words, in order to grow, we must do things before we know how to do them. As educators, we can relate to our students as “a head taller” (a little beyond themselves) as ever-growing, ever-becoming, moment-by-moment.[5] This is what we mean by “performance”: even if we think or know that a student is not yet capable or knowledgeable about certain things, we act as if they are. Relating to student in this way enables and facilitates their learning and growing.

The performance of relating to others ahead of themselves is something we can do in our classrooms, research labs, during individual meetings, or in the field (e.g. collecting samples in a forest, during a museum visit, as part of a community-based project, or as part of study abroad). Regardless of the location, as the teachers, we help set the tone by affirming and being encouraging of each and every one of our students by relating to them just ahead of themselves—an activity that builds their confidence. Interestingly, we can do this regardless of whether or not we think our students are fully capable of doing the particular task at hand. For the student of History, the task might be interpreting the political content of a 17th century Portuguese document from the Indian Ocean world; for the student of Chemistry, the task might be using a mass spectrometer to analyze a sample. This suspension of absolute certainty (of “knowing”) is the performance on our part. In an ongoing way, we practice and encourage others to perform by having a developmental posture about our student’s abilities and disposition.

For example, Nadja’s chemistry group researches new ways to combat infections. In the context of this particular research group, she relates to all of her group members—undergraduates, graduate students and postdoctoral researchers—as if they are scientists (embodying obuchenie). That is, she helps create a culture in her group meetings in which she and students perform as scientists. She pairs junior and senior researchers, the latter learning to follow her lead by interacting with the junior members as if they are capable just beyond their knowledge and training. Notably, in Nadja’s group meetings, each student, no matter how junior, presents the results of his or her experiment just as a senior scientist would. In this way, the students learn (by doing, performing) to speak, act, and think as scientists.

Indeed, those who interact with Nadja’s students often comment on the unusual dynamic of her group—that is, the dynamic that Nadja and her students co-create. For instance, on a recent visit, UNCG Chancellor Franklin Gilliam, Jr. remarked that he “could not tell the difference between undergraduate and graduate students explaining their work.” That is, by students being related to as fellow scientists, they become scientists (or certainly have a better chance of becoming scientists than if they were related to as incapable of such). Indeed, more than half of the students in Nadja’s research group go on to careers as research scientists after graduation. Put another way, the students-becoming-scientists improvise their way into becoming scientists just as toddlers babble their way into becoming language speakers. In both contexts, this transformation occurs through interactions with others who are more developed (senior scientists and language speakers, respectively).

Like Nadja, Omar runs his own group: a weekly philosophy and community organizing meeting of former and current students—another kind of experiential learning opportunity. Participants discuss whatever anyone brings into the meeting—the latest news, an experience they had, something they read. The concept of “Yes, and” is explicitly referred to as part of creating the environment in Omar’s group. His meetings involve working on the logistics of community organizing efforts, in effect helping to take the culture that they create together to larger spaces in the university and the broader community.

Over the past three years, Omar’s philosophy group has helped to produce three ongoing community-building programs. The first of these is Community Play!/All Stars Project, a free monthly series of workshops, classes, and cultural outings in the poor and working-class Warnersville neighborhood near the UNCG campus. Another project is Bridging the Gap, university workshops with students and UNCG Police officers three times per semester that use performance and improvisation to create environments for conversation. Finally, there is Monday Play!, a weekly improv session on campus involving students, faculty, and staff. While some students from Omar’s group have continued on to graduate programs in human development and family studies, sociology, social work, and law school, as importantly, the improvisational (“Yes, anding”) skills that they learn through practice are transferable to many areas of life—academic and otherwise.[6]

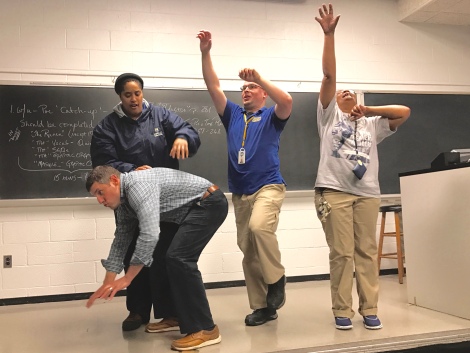

Dabbing participants in a UNCG campus “Monday Play!” activity.

Engaged Experiential Learning

Following the work of Vygotsky, as articulated by Holzman and Newman, we understand development as not something that happens to people but something that is created by people. The methodology we practice to support the development of our students is a form of experiential learning that we call engaged experiential learning, emphasizing an active process of participation. We can create this with any grouping of people. The group can be as small as a one-on-one meeting, or a class full of students, as long as it affords members of the group to develop through interaction. In such groups, those who are less developed in one area of study or life can creatively imitate those who are more developed. The teacher serves as a leader and facilitator of this activity by affirming those who are stretching (doing something unfamiliar and challenging) and encouraging others, by leading through example, to do so as well.

Effective experiential learning environments are those in which students explore new ideas and ways of being with the support of others to do so. “Yes, and” helps to create such environments. And while it is possible to create such developmental learning environments in the classroom, we find that non-assessed spaces (where grades are not an overbearing factor), allow for students to more safely express themselves and take creative, intellectual, and emotional risks. Nadja’s research group and Omar’s philosophy group are examples of this. In an assessment-filled world (be they grades or their close equivalents), creating non-assessed spaces is a vital part of students’ development.

Our experience is that effective group learning is not assured by simply assembling students together. That is, a group is something to be created, not a given. It is largely the responsibility of a group-in-the-making leader (the teacher) to create an engaged learning environment by setting the tone and attentively cultivating the space where all in the group can grow—in other words, creating a developmental culture. “Yes, and” enables this creative moment-by-moment activity.

Do our students sometimes say things that are “incorrect” or “wrong” in a given context? Yes, of course. When this happens, we resist the temptation to negate what they have said and instead find positive ways of framing a response in which what they have said is of value. Let us also consider the following: Students tend to assume we are correct—even if we might not be. Given the power dynamics between “professor” and “student,” they give us the benefit of the doubt or do not challenge us even if they sometimes suspect we have made a mistake or are “wrong.” They do this for us, and we should do the same for them, even if we are certain that they are “wrong.” This building activity, as opposed to tearing down, is the creative essence of “Yes, and” and the gist of what we see work in and out of the classroom in supporting students’ development and what they are able to learn.

Further, there is an obvious but related important point to make regarding power and our institutional and social roles, which is that students often feel shutdown—or even purposefully made to feel dumb—by professors. Faculty sometimes believe that their job is to be critical of students in a negative way. The point we are making here is how to critically engage in a way that is as effective as possible for students to learn and grow. As noted, we believe that staying positive, even when disagreeing or pointing out something that may not be correct, is simply more effective. Why? Because it builds trust between the professor and student (or professor and the class as a whole). When trust is established, students are more willing and able to hear criticism and grow from such criticism. Put another way, students are more open to being coached, directed, or redirected when a relationship has been established in which students experience professors as being there to support them, not attack them or make them feel dumb or humiliated.

Some examples of positive responses using “Yes, and” both in and out of the classroom might be “That’s an interesting way of looking at it …”; or “I hear what you’re saying …”; or “Yes, I like where you’re going with that, tell me more …” This last response is particularly helpful because it provides an opportunity to highlight the aspect of the response that seems the most helpful and plausible. It is then possible to guide the discussion in a productive direction, building on what a student brings to the conversation.

Omar’s Philosophy and Community Organizing Group, a non-assessed (ungraded) weekly gathering of UNCG students read and discuss an article together (with Nadja as guest).

“Yes, and” in the Classroom

As a way of demonstrating what “Yes, and” looks like, Nadja carries out the approach with three chemistry students in one of her classes:

Nadja: Why do you think that compound A moves down the column faster than compound B [in gas chromatography]?

Joe: Maybe because it is smaller? Don’t smaller things move faster?

Nadja: OK . . . yes, I like where you are going with that, and size can be important. What other factors can be influenced by size?

Cindy: What about polarity?

Nadja: Absolutely! Polarity is super important here. What else? Anyone?

Josh: What about boiling point?

Nadja: Excellent. Molecules with the lowest boiling point generally move fastest in gas chromatography because they evaporate quickly, spending more time in the gas phase. Joe’s point about size is also a really good one, though, because smaller molecules tend to have lower boiling points. But, size isn’t the only factor that influences boiling point, right? What else is important? Cindy, this is back to the point you made . . .

Cindy: Polarity?

Nadja: Yes, exactly! Polarity. So, Cindy or someone else, how does polarity influence boiling point?

In this example, only Josh had what was technically the “correct” answer. But, there was also a useful element in both Joe and Cindy’s answers. By highlighting this (practicing “Yes, and”), it was possible to acknowledge the contributions Joe and Cindy made, with the intention of leaving them feeling affirmed rather than shut down. Importantly, Nadja referenced both Cindy and Joe by name in her responses, a way to hold their attention, draw them further into the discussion, and highlight the importance of their contributions.

The focus in higher education is overwhelmingly on content with less attention to context. However, the way in which content is delivered, we suggest, will shape if not determine whether it will actually be learned (received and understood). Practicing “Yes, and” can help create a supportive, affirming environment in which students may more effectively learn content.

The “Yes, and” approach is what we tend to do quite naturally with small children. For instance, when a child presents us with a painting, we’ll say, “Oh, what a beautiful painting!” We might add, “I especially like the grass next to the house.” It’s immediate and simple. We wouldn’t normally say, “That does not look like a flower; it’s way too big relative to the house and your color and overall perspective is off!” With children we acknowledge and affirm, and we do so enthusiastically. We are suggesting that this is an activity we can also do with our students, no matter their age—that is, if we want to encourage their continued learning and development.

The type of positive responding to students in the classroom, lab, or group meeting that we describe here is actually what some of the best teachers do—even if they don’t think about it in these explicit terms. There are many professors who often improvise using positive affirmation. Unfortunately, equally as common, and especially in academia, is a negative style of interaction, in which professors respond to students (and their colleagues) not with “Yes, and” but rather with “No, because.”[7] Rather than inspiring or encouraging learning, “No, because” responses tend to impede the learning process, leading the person who has been negated to withdraw.[8] As an antidote to this negatively critical, uninspiring, and less effective way of relating, educators can intentionally adopt the practice of “Yes, and” as an approach to be carried out consistently. For teachers not used to relating in this way, the performance of “Yes, and” may at first feel uncomfortable and awkward. However, relating in affirming ways gets easier with practice, and eventually—in our experience—becomes part of what one “naturally” does with students. Ultimately, what we are proposing is that “Yes, and” is a learnable approach, and that any teacher can become more effective by practicing it.

Nadja and her Chemistry Research Group pose as cartoon characters for a group photo, demonstrating that one doesn’t have to be too serious to do good science.

“Yes, and” in the Public Sphere

Omar is often asked to facilitate public conversations on “hot-button” issues. Recent topics include police-community relations, Islamophobia, xenophobia, and racism. In the same way that we use “Yes, and” in the classroom, Omar also practices this approach in public conversations. As a way of demonstrating what this looks like, here is dialogue from a forum on campus between students and police officers, with Omar as moderator.

Omar: Ok, Zach, go ahead.

Zach: Look, the police treat us like criminals . . . yesterday I was minding my own business and one of those campus warnings went out about another “black male suspect” having done something. Of course, I was . . .

Officer Herring: We are here to protect you . . .

Zach: No, you’re . . .

Omar: Ok, ok, so Zach is upset—and rightly so! AND, so is Officer Herring. Zach, Officer Herring is saying that he’s trying to protect you . . . So what do we make of this?

Officer Herring: The law requires us to give accurate descriptions of suspects.

Omar: Yes, and it’s deeply, deeply, upsetting to many people on campus, including the very people right here, starting with Zach . . . And it’s upsetting to me.

Zach: [Looking directly at Officer Herring] Do you even know what it’s like to be targeted and told again and again that somehow you’re to blame, that you’re the criminal, just because you exist?

Officer Herring: Actually, yes, I do. When I’m in uniform people treat me like I’m the bad one.

Zach: That’s cause you kinda are [applause from many in the audience].

Omar: I hear you Zach, and it’s also the case that Officer Herring is sitting right here with you, with all of us, to have a discussion. What do you make of that?

Zach: Well, I’ll give him credit for that.

Omar: And we should . . .

In this example, Omar’s affirming (“yes, and”) responses to both Officer Herring and Zach allow the group to begin to experience a way of seeing things that is less binary and oppositional. By modeling a response that acknowledges, in this case, two different viewpoints, and relating to the group as a whole even while speaking directly to the officer and the student, Omar facilitates a collaborative way of interacting. Importantly, this focus on affirming and building with the group requires a suspension of the need to get to some “objective truth” or determine who is “right” and who is “wrong.” As moderator, Omar could have made a different choice in how he responded to Officer Herring. Drawing on his progressive education and experience with issues of racial justice, he could have pointed out the false equivalency between the stereotyping faced by people of color and that faced by police offers in uniform. Many would agree that by doing so Omar would have been right. However, to shut down the police officer with a “no, because” response would have been to stop the conversation and miss out on an opportunity for growth and development of the group. Keeping the conversation open to multiple perspectives (rather than one “right” way of seeing things) allows for the possibility of a deeper understanding for all involved. And while deeper understanding may not lead to justice (or perceived justice) at the macro- or institutional level, in an immediate sense, it helps to diffuse tensions. As importantly, it builds a relationship between participants that might make all the difference, at a later time, if they are confronted either directly with each other, or with officers or young people who remind them of each other.

Nadja, UNCG students, and police officers play an improvisation game as part of a Bridging the Gap workshop organized by Omar’s Philosophy and Community Organizing group.

Engaged Experiential Learning as Developmental

By affirming our students we are not being easy on them. Au contraire! The relationship of mutual trust that develops between group members as we acknowledge each other (and our views) enables all participants to stretch and grow. Indeed, by focusing on the relationships between ourselves as teachers and our students, we are able to be even more challenging of each other. It is this relational foundation that allows us to effectively give and receive constructive criticism, to take creative, intellectual, and emotional risks, tackle new challenges, and become ever-more resilient and creative. For example, in the student/police forum that was presented earlier, Zach was a student of Omar’s with whom he had developed a level of trust. Because of this relationship, it was possible for Omar to call on Zach by name and to encourage him to be open to engage with Officer Herring. Importantly, the relationship between Zach and Omar also served as a starting point for the establishment of rapport with other students and police officers participating in the forum.

We understand that our being unflinchingly affirming of our students flies in the face of the epistemological bias in academia—that is, we as professors being certain of things (a.k.a. being the knowers).[9] What we are suggesting here is an ontological shift (a shift that requires action)—that is, when it comes to teaching and mentoring, to move away from teaching as the imparting of knowledge to teaching as developing relationships. The nature of building relationships is improvisational, building with what is given and then responding. Such improvisation, however, does not happen in a vacuum. Like a jazz musician or a modern dancer, we base our moves on past experience and training. There are things that we have tried and seen that have worked or not, from which we draw upon. We also try new things on the spot or imitate what we’ve seen others do. Throughout all of this, the spirit of what we do is “Yes, and.”

Our students often speak to the positive impact that participation in our groups has had on their development. For example Nadja’s former student Joseph Egan grew up in a working-class town outside of Detroit and is now pursuing a Ph.D. in Chemistry. As a child, Joseph fully expected that his future would revolve around assembly line work. Instead, he is on a different path, that of a research scientist. In talking about his experience as a student in Nadja’s research group, Joe says, “the group has always had something that just made every day an awesome experience and got me so excited about science. It literally redirected my entire life.”

Omar’s former student Domonique Edwards is another example. Domonique is a first-generation Guyanese-Jamaican American from a largely black working-class town near Charlotte, North Carolina. A double-major in Dance and Psychology at UNCG, Domonique helped to create Community Play!/All Stars Project. Domonique went on to become class valedictorian and has embarked on her Ph.D. in Human Development and Family Studies. She considers participation for several years in the philosophy group with Omar to have been a critical part of her development. Domonique describes the gatherings as a place where she “learned to create philosophical conversations with others, not knowing what [she] was doing, but doing it anyway.” Her words are both a testament to the improvisational nature of the meetings and the impact such meetings had.

Like many educators, we seek to inspire in our students flexibility, open-mindedness, resilience, and the ability to foster healthy relationships. Our aspiration for our students is not merely that they acquire specific technical skills—for instance, operating scientific equipment, solving differential equations, or doing textual analysis. Nor do we see it as our sole responsibility to expose them to a particular cannon of knowledge that must be learned and memorized. Rather, we expect our graduates to be creative learners, skilled at seeing connections in an extremely data-rich world, and able to discover and do things that are yet unimagined. Building on their experiences with us, our graduates can live (continue living) fulfilling lives and contribute to the development of society as a whole. In small but meaningful ways, the co-creation of developmental learning environments—that is, engaged experiential learning—using “Yes, and” as a methodology, helps us help our students pursue their interests and make the world they want to live in.

Omar, his former student Domonique Edwards (far right) and participants in “Community Play”, an outreach program that uses improvisation and play to build community in working class neighborhoods in Greensboro, NC

Practicing “Yes and”

Download Omar Ali and Nadja Cech’s list of 11 ways to practice “Yes, and” teaching (PDF).

Notes

[1] “Yes, and” is a guiding principle in improv theatre; two others are “make your partner look good” (setting them up for success) and “go with the flow.” The essence of these three principles may be captured in the first, “Yes, and”—the method and approach that describes and guides our pedagogy. Note that affirming is not the same thing as agreeing; the focus is on creating something with the other person. This approach is also consistent with what Clegg and Rowland refer to as “kindness in pedagogy”; Sue Clegg and Stephen Rowland, “Kindness in pedagogical practice and academic life,” British Journal of Sociology of Education, Vol. 31, No. 6 (2010): 719-735.

[2] Sheryl Scrimsher and Jonathan Tudge, “The Teaching/Learning Relationship in the First Years of School: Some Revolutionary Implications of Vygotksy’s Theory,” Early Education and Development, Vol. 14, No. 3 (July 2003): 293-312. In 2009 Tudge noted that a dash between “teaching” and “learning” might be a better way of expressing obuchenie, since it avoids the forward slash meaning “either/or” when the Russian term actually “signals a multifaceted approach for which English does not have an equivalent” (Correspondence from November 17, 2009).

[3] Lois Holzman, Vygotsky at Work and Play (New York: Routledge, 2008), 18.

[4] While closely related, “learning” and “development” are slightly different things. Development is more a capacity while learning involves acquiring particular knowledge or carrying out a particular skill (for instance, I may have learned how to bench press my own weight using a certain technique, but I am not physically developed enough to bench press twice my weight; or, I may have learned how to say “good morning” in Chinese, but I may not be linguistically developed enough to use this in a variety of sentences in Chinese). Fred Newman and Lois Holzman, The End of Knowing: A New Developmental Way of Learning (London: Routledge, 1997), 111.

[5] Ibid., 110-112. As Vygotsky notes “in play it is as though [the child] were a head taller than [themselves].” L. S. Vygotsky, Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes, Michael Cole, Vera John-Steiner, Sylvia Scribner, Ellen Souberman, eds. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978), 102.

[6] After visiting UNCG, Lois Holzman graciously observed “Ali embraces performance as not only an effective pedagogy but equally as a new type of university culture and an activity that bridges campus and community.” Holzman gave the keynote address at the 2016 North Carolina Honors Association conference hosted by Lloyd International Honors College at UNCG on the theme of “Innovations in Pedagogy, Research, and Learning”; she offered comments in an article published soon thereafter; Lois Holzman, “Play is Movement,” Social Therapeutics (October 10, 2016) http://loisholzman.org/2016/10/play-is-movement/

[7] See F. Gregory Ashby and Jeffrey B. O’Brien, “The Effects of Positive and Negative Feedback on Information-Integration Category Learning,” Perception and Psychophysics, Vol. 69, No. 6 (2007): 865-878; “Feedback: Negative, Positive, or Both?” The Teaching Professor Blog, Faculty Focus: Higher Ed Teaching Strategies (August 26, 2010).

[8] As Clegg and Rowland note, “[students] respond to kindness and to its absence, or worse, where people appear unkind,” 732.

[9] Fred Newman and Lois Holzman, The End of Knowing: A New Developmental Way of Learning (London: Routledge, 1997), 76, 169.

Photo of stage by H.T. Yu (CC-BY-SA 2007)

Omar H. Ali is Dean of Lloyd International Honors College at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro and the 2016 Carnegie Foundation North Carolina Professor of the Year. A historian of the African Diaspora in the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds from the early modern period to the present, his latest book is Malik Ambar: Power and Slavery Across the Indian Ocean, published by Oxford University Press. For more, see his faculty website.

Omar H. Ali is Dean of Lloyd International Honors College at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro and the 2016 Carnegie Foundation North Carolina Professor of the Year. A historian of the African Diaspora in the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds from the early modern period to the present, his latest book is Malik Ambar: Power and Slavery Across the Indian Ocean, published by Oxford University Press. For more, see his faculty website.

Nadja B. Cech is Professor of Chemistry at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro and recipient of The College of Arts & Sciences’ Teaching Excellence Award and the Thomas Undergraduate Research Mentor Award. She is Director of the Institutional National Service Award “Innovative Technologies for Natural Products Research,” a predoctoral training program funded by the National Institutes of Health. For more, see the website for the Cech Research Group.

Nadja B. Cech is Professor of Chemistry at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro and recipient of The College of Arts & Sciences’ Teaching Excellence Award and the Thomas Undergraduate Research Mentor Award. She is Director of the Institutional National Service Award “Innovative Technologies for Natural Products Research,” a predoctoral training program funded by the National Institutes of Health. For more, see the website for the Cech Research Group.

Pingback: East Side Institute » “Yes and…” as Teaching-Learning Methodology·

Pingback: Yes, and as Teaching-Learning Methodology·