In 1982, Nancy Sommers published the landmark, award-winning essay “Responding to Student Writing.” That essay has helped many teachers think more intentionally and act more skillfully when they respond to what students write. Sommers shows how teachers too often write comments that come off as “arbitrary,” “idiosyncratic,” “contradictory,” and even “mean,” even though they put a lot of time and attention into commenting (p. 149-50). While the essay gives a needed call to pay more attention to how and why we comment, it comes off a bit hard on teachers, perhaps unjustifiably so in some cases, as Howard Tinberg has noted (p. 263). Now, thirty years later, Sommers takes up the same questions in a more positive, more practical, and more fully developed way, in her new book, Responding to Student Writers.

In the introduction, Sommers establishes the value of assigning and responding to student writing. She describes a large study she conducted at Harvard that followed four hundred students through four years of writing in college. She and her colleagues collected “more than 600 pounds of student writing and five hundred hours of taped interviews” from the students. Among other things, they looked at how different professors respond. Quite a range of ways of responding emerged: “papers returned with no response, just a grade; papers returned with bewildering hieroglyphics; and papers returned with responses that treat students like apprentices, engaging with their ideas, seriously and thoughtfully.” Afterward, when they asked students about “their best writing experiences,” “two overriding characteristics emerged” in the answers. First, students valued “the opportunity to write about something that matters” to them. Second, they valued “the opportunity to engage with an instructor through written comments.” Sommers concludes that “teachers’ comments play a much larger role than we might expect” (p. xiii).

The most useful and insightful points of the book, in my view, are where Sommers defines the purpose of responding to student writing. At the start, she quotes William Zinsser on this: The “ministry” of responding “is not just to the words, but to the person who wrote the words” (x). This quote speaks to the shift from responding to student writing to responding to student writers in Sommers’ titles. For me, this statement by Zinsser is one of those that instantly flip everything I’m used to thinking on its head; it is so obviously true that I wonder why I never thought of it before. Even if I had at least in part practiced the principle behind the statement, I had never understood or articulated it in just that way. What our students write does not dictate how we respond. What our students need does.

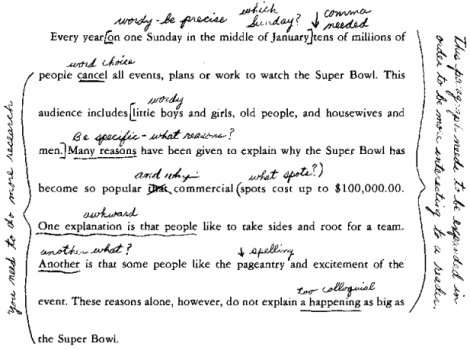

Sommers offers this marked passage as an example of contradictory teacher feedback. The comments between the lines ask for specific corrections, while the ones in the margins make copy editing premature by asking for the whole paragraph to be reworked. (“Responding to Student Writing,” p. 150)

In the spirit of Zinsser’s statement, Sommers proposes that our comments should aim to “teach one lesson at a time.” We should “ask ourselves: What single lesson do I want to convey to students through comments? And how will my comments teach this lesson?” (p. x). The lessons we choose should be “portable” ones, lessons that students can carry with them to future writing assignments (p. xiv).

Sommers’ insistence on using comments to teach students one lesson at a time (later she loosens up to “one or two” lessons) may be hard for many to accept. So often, student writing begs for many lessons all at once. But Sommers’ rule (rule of thumb, of course) puts into practice two insights. First, when we follow the one lesson rule, commenting becomes more manageable for us, while learning from our comments becomes more plausible for our students. Commenting too much burdens us without helping our students. They can only take in so much at a time.

Second, when we follow the one lesson rule, teaching becomes our purpose. Commenting is not a clerical duty; it is an act of pedagogy. We do not help balance any cosmic scales by commenting on something just becomes it “needs” to be commented on. We should not respond just because students have written, because they have written well, or because they have written poorly. Instead, we should respond because we want to teach them something that—as best we can tell from reading their work—they need and are ready to learn.

With these principles established, Sommers goes on in the chapters of the book to offer practical advice on writing marginal and end comments and on managing the paper load, using rubrics, and so forth. She shares and discusses examples of responses along the way. The book is smart and readable, stimulating and enjoyable. And helpful. It is also very short (less than 50 pages). Best of all, it is available for free for teachers from Bedford/St. Martin’s. Anyone who responds to student writing/writers should either request a copy of the book or download it as a PDF and read it right away.

Beyond the Red Ink

In Beyond the Red Ink: Teachers’ Comments through Students’ Eyes, a video Sommers produced, students at Bunker Hill Community College talk about receiving comments on their writing.

Across the Drafts

In “Across the Drafts,” Sommers looks back on “Responding to Student Writing” and revises her stance. She also describes in more detail the longitudinal Harvard study, particularly its findings on the complex role that feedback plays in the “slow” process of “writing development” (p. 250). Several passages stand out:

The movement from first-year writing to senior, from novice to expert, if it happens at all, looks more like one step forward, two steps back, isolated progress within paragraphs, one compositional element mastered while other elements fall away. (p. 249)

[F]eedback plays a leading role in undergraduate writing development when, but only when, students and teachers create a partnership through feedback—a transaction in which teachers engage with their students by treating them as apprentice scholars, offering honest critique paired with instruction. (p. 250)

[F]eedback shapes the way students learn to write, but feedback alone, even the best feedback, doesn’t move students forward as writers if they are not open to its instruction and critique, or if they don’t understand how to use their instructors’ comments as bridges to future writing assignments. (p. 254)

Thank you for the summary of Sommer’s new book. It brings to mind an article that I recently blogged about (http://metisllc.com/teaching-strategies-for-the-biology-classroom-and-beyond/ ). In her article, Tanner suggests methods to promote a classroom where all students feel equally valued. Several of her suggestions had to do with writing– giving assignments, even if it’s just a comment about the day’s lecture, keep students more engaged and give the teacher opportunities to address the specific needs of students. I think her article falls right in line with this book, especially her points about trying not to do too much and being careful about harshly judging student responses.

Thanks for sharing the link, Metis. I think you’re right. There are some key continuities between what Tanner and Sommers say. Particularly this, I think: the point isn’t just to teach students but to empower students as learners.

Absolutely. I’d be interested in hearing more of your thoughts about teaching strategies– particularly related to active learning. If you’d ever like to guest blog for us (www.metisllc.com/blog), please contact me (Emily) at metis.birding@metisllc.com. We’d be happy to return the favor!

Reblogged this on The Writing Campus and commented:

“Teaching and Learning in Higher Ed.” highlights some of the best practices from Nancy Sommers’ new book, Responding to Student Writers. One of the most helpful insights is the ability to recognize that our comments to students may be contradictory, misleading, or vague, and that the real purpose of offering feedback to students is to “teach one lesson at a time.”

“We should ‘ask ourselves: What single lesson do I want to convey to students through comments? And how will I teach this lesson?'”

Pingback: How Can I Talk with Writers Who Are Students? | Fragments·

Pingback: Error in Student Writing: A Balanced, Developmental Approach | The Writing Campus·